Abuse Among Disability Communities Part 3: Autism and Abuse

Autism Spectrum Disorder is a common developmental disability. Like people with TBI (traumatic brain injury), people with Autism are vulnerable to abuse in unique ways, due to the ways in which many people—even those working in schools and social services—misunderstand Autism, and to the communication barriers that sometimes arise between Autistic and non-Autistic people. Other reasons include the power differential between people with Autism and without Autism (people who are neurotypical), which can make it difficult for people with Autism to report cases of abuse with confidence that they’ll be believed.

A blogger who self-identifies as Autistic summarizes the dilemma commonly faced by Autistic people in abusive relationships: “If you are naturally trusting, it’s so very easy to get trapped in an abusive relationship. If you have trouble communicating, it’s so very hard to get out.”[1] Some Autistic people do not speak, and some Autistic people use coded language that reflects their own interpretation of language rather than more widespread colloquial ways of speaking. One example of a specific communication style some Autistic people use is to quote books and movies rather than forming unique sentences. The quotes may still reflect a feeling or thought that the speaker wishes to communicate, but to someone who is not paying attention, it may just sound like mindless repetition of words that the speaker has heard before.

People with Autism sometimes communicate non-verbally as well. A young man I interviewed, who was diagnosed with Autism Spectrum Disorder as a child, described a situation in which he was stimming (a term used to describe repetitive motions or sounds a person makes, in order to calm anxiety, focus, express emotion, or relieve sensory overload[2]) by making a noise, and an instructor at his college threatened to call public safety because his constant noise was inappropriate for the classroom. As he described it, he was covering his ears and making a noise in order to tune out an argument that was taking place nearby. His instructor did not understand why he was doing that, and so she reacted with anger and threats.

The same young man described how, when he was in his late teens, an older man approached him at a department store, told him that he needed help, and asked this teenager to follow him out to his car. Someone saw him following the man, and stepped in.

Not all Autistic people are “naturally trusting,” as the blogger cited earlier described. However, when you have been taught, as many people with cognitive or psychosocial disabilities have, that your brain is not trustworthy and that neurotypical people’s brains work normally, then it can be difficult to call out other people for harmful behaviors.

This is why it is helpful for everyone, regardless of whether or not you know someone who is Autistic, to be familiar with Autism and neurodiversity in general. When it comes to recognizing signs of abuse, protecting someone from abuse, or avoiding being unintentionally abusive, it is important to recognize that different people’s neurological makeup make them more sensitive to certain things. This means that abuse can constitute different actions for different people, depending on what triggers someone has.

Another reason that it is helpful for everyone to recognize characteristics of neurodiversity, is that they can sometimes blend in with signs of trauma, and it is important to know what behaviors are warning signs of abuse, and what behaviors are more commonly related to Autism or other categories of neurodiversity.

When I worked in an after-school program in a high-poverty neighborhood where violence was common, I encountered children who exhibited high levels of sensitivity to external stressors such as loud noises and physical contact (such as if someone brushed their arm while walking past). Some of the children’s heightened levels of sensitivity were related to experiences that they had had in the past: seeing or experiencing violence, hearing gunshots nearby, recognizing what sort of shouting means danger, are all ways in which some children’s environments had increased their sensitivity to noises. But a couple of the children I worked with exhibited signs of neurodiversity outside of the clear and typical signs of trauma.

Speaking with parents, I learned that one of the children had been identified as Autistic by the school, and another child’s mother was hoping for the same for her son, so that he might get the learning supports that he needed. In that environment, however, staff often attributed the heightened sensitivity of Autism to the post-traumatic stress that many of the students exhibited based on their environments. Not differentiating between responses to noise or other stimuli that stemmed from trauma, and responses related to Autism, made it difficult to figure out whether or not a child was in danger of, or already experiencing abuse. Furthermore, it made it difficult to provide a safe space for the children to learn and to express themselves.

In order to be trauma-informed in an effective way, it is important to be aware of neurodiverse conditions such as Autism. People with Autism can be vulnerable to abuse in the same ways as neurotypical people, but also in different ways. People with Autism might also exhibit sensitivity that seems similar to trauma responses to noise and other stimuli. Knowing what to expect when interacting with a person with Autism can help neurotypical people to be receptive to what Autistic people are communicating. And it can help break down misconceptions of what behaviors are to be expected and what behaviors are signs of abuse.

For more information on Autism, I recommend the Autism Self Advocacy Network, which is a direct source to read Autistic people’s writing about their own experiences: https://autisticadvocacy.org/about-asan/about-autism/.

Written by Anna Clements

Sources:

[1] https://chaoticidealism.livejournal.com/65514.html

[2] https://www.spectrumnews.org/features/deep-dive/rethinking-repetitive-behaviors-in-autism/

Traumatic Brain Injury, or TBI, is a common condition that often goes undiagnosed. It is defined by the Center for Disease Control as a disruption in the normal function of the brain, often caused by a bump to the head[i]. It can result in headaches, fatigue, memory loss or difficulty retaining new memories, insomnia, reduced mental processing speed, reduced attention span, difficulty thinking of the right words to communicate, and a host of other effects.

In recent years, athletes and veterans have called attention to the prevalence of TBI as a medical condition. Still, wider awareness is needed, particularly in situations involving domestic abuse. TBIs can be caused by abuse; they can also make people more vulnerable to abuse. Knowing what to look out for can make a difference in identifying a traumatic brain injury, treating and accommodating it, and protecting people who have it from being in greater danger.

If someone has lost consciousness from a blow to the head, then it is likely that they have suffered some sort of TBI, whether mild, moderate, or severe. One of the difficult parts of identifying a traumatic brain injury is that when a person has one, they are not always immediately aware of the changes that their own brain has undergone; it is often up to the people around them to pick up on differences in their memory, processing speed, or attention span.

An anonymous TBI survivor states: “Over a decade after my brain injury, I’m still not always aware of how it affects me. Because my memory is damaged, I blank out on the things I do that show that my injury is still present. I’m sometimes unaware of those behaviors until someone else points them out to me.” Because it can be difficult to assess the differences in your own brain, it is important to seek help, to talk to other people about what you are experiencing.

For someone who is experiencing abuse, a brain injury can be particularly dangerous. Partners of people with TBI are often their go-to person to help compensate for the memory issues and other effects. But if the partners are abusive, then that help can become toxic. Imagine if you saved your memories in a computer that had a virus which edited the things you type to reflect a different perspective on the memories—one that shifts the responsibility for things that go wrong away from the person who caused them and onto you.

Along with the cognitive effects of a traumatic brain injury, there are often emotional repercussions as well. Another TBI survivor describes it as “the death of my old self.” She elaborates, “I entered into a dark period of not having a strong sense of self. I was estranged by this cognitively compromised person I had become. It took time to patchwork together a new sense of self.” During a transitional time such as that, it is important to be surrounded by supportive people.

This is just one of the reasons why staying quiet is not an option. Some of the damages and risks of abuse might be physically observable, but other injuries are invisible, and show up in a person’s behavior. If you notice someone showing the cognitive or psychological signs of abuse, it is important to reach out and get help. Encourage them to call our 24-hour hotline at (269) 673-8700 or 888-411-7837, or reach out to us yourself for advice and resources.

Getting help after a TBI can include many things. Speech therapy, occupational therapy, physical therapy, and psychological therapy all help people with brain injuries get their lives on track. The Michigan Public Health Institute has compiled a guide to resources in the state, along with information and advice on how to find and access services. This guide can be found here: https://www.michigan.gov/documents/mdch/Michigan_Resource_Guide_V3_201402_7.pdf

Once a TBI has been identified and documented by medical professionals, the person who has it is often eligible for workplace or educational accommodations. This can mean having a quiet space to work or study, having extended time on deadlines, assigning a point person to help collect and remember important information, and flexible scheduling, to name just a few. Identifying a traumatic brain injury can help others understand the struggles that someone is facing, and to develop strategies to overcome those struggles.

It is difficult to estimate the prevalence of TBI because not everyone knows when they have one. But for anyone who has experienced violence, being aware of the existence of a traumatic brain injury and the effects to watch out for could mean a changed life.

Written by Anna Clements

[i] https://www.cdc.gov/traumaticbraininjury/index.html

People with disabilities are vulnerable to abuse in unique ways. According to the American Psychological Association, women with disabilities are 40 percent more likely to experience intimate partner violence than women who do not have identified disabilities[i]. And although the cases are less frequent, men with disabilities are also vulnerable to physical and sexual abuse[ii].

There are several reasons behind these statistics. One of the reasons involves the caretaker roles that some partners of people with disabilities take on, which shifts the power dynamic and puts the partner who provides care in a position of control[iii]. Another reason that people with disabilities are particularly vulnerable to abuse relates to widespread misunderstanding of the relationship between the right to autonomy and the need for assistance; both abusers and people being abused don’t always understand that people who provide care cannot legally use that to claim authority over those who receive care[iv]. And a third reason is that people with disabilities who experience abuse do not always know of a safe alternative care provider to the person who is abusing them. Whatever the reason, it is clearly an issue that calls for wider awareness, in order for people to be equipped with the knowledge to recognize abuse and step in when necessary.

For people living in group care facilities, patterns of abuse can be particularly hard to identify, as the boundaries between residents and the staff who provide assistance are less concrete than in most professional relationships. For instance, support staff often assist residents with bathing and general personal hygiene routines, which makes physical interaction a common phenomenon. Although Michigan’s mandatory recipient rights trainings make it clear to care staff that the people receiving care are in charge and cannot legally be coerced into any physical interaction, the care staff sometimes hold informal authority based on differences in physical or mental abilities, placing them in a position of power[v].

According to Michigan’s Mental Health Codes, staff at residential facilities are required by law to report any suspected abuse that they observe. Other people who observe possible cases of abuse, even if they are not staff, are still encouraged to report cases of suspected abuse, and will not be penalized for false reports if the reports were made in good faith[vi]. Anyone can report abuse, and everyone should feel able to do so. The Michigan Department of Health and Human Services has a 24-hour line for reporting abuse of vulnerable adults (which includes adults with disabilities). This number is 855-444-3911.

According to Michigan’s Mental Health Codes, staff at residential facilities are required by law to report any suspected abuse that they observe. Other people who observe possible cases of abuse, even if they are not staff, are still encouraged to report cases of suspected abuse, and will not be penalized for false reports if the reports were made in good faith[vi]. Anyone can report abuse, and everyone should feel able to do so. The Michigan Department of Health and Human Services has a 24-hour line for reporting abuse of vulnerable adults (which includes adults with disabilities). This number is 855-444-3911.

It is important to remember that adults with disabilities are adults, regardless of whether the disabilities are mental or physical, and that although they may have caretakers, they are not children. Adults with disabilities can legally engage in consensual sexual activities. Having a disability might make a person more vulnerable to abuse, but that does not mean that their right to be sexual should be taken away. Consensual sexual activities are legal between two adults, regardless of disability, as long as one of them is not coercing the other. However, if there are doubts over whether a person is being coerced into a sexual situation, it is always best to reach out for help or legal advice.

As with any population, in order for people with disabilities to be safe from abuse, they need to be informed as to what constitutes abuse. This means knowing the vocabulary to articulate their experiences. For a person to describe an abusive encounter, it is useful for them to know the words for body parts and for actions. Elevatus Training, a company specializing in sexual education for people with disabilities, has put together a list of articles and other resources on sexuality and disability, available here: https://www.elevatustraining.com/resources-2/helpful-articles/. Sexuality education gives people the power to call the shots, to communicate what they like and don’t like, and to know and report if they are being sexually abused.

As with any population, in order for people with disabilities to be safe from abuse, they need to be informed as to what constitutes abuse. This means knowing the vocabulary to articulate their experiences. For a person to describe an abusive encounter, it is useful for them to know the words for body parts and for actions. Elevatus Training, a company specializing in sexual education for people with disabilities, has put together a list of articles and other resources on sexuality and disability, available here: https://www.elevatustraining.com/resources-2/helpful-articles/. Sexuality education gives people the power to call the shots, to communicate what they like and don’t like, and to know and report if they are being sexually abused.

To summarize, adults with disabilities are vulnerable to physical and sexual abuse, but that does not mean that they should be denied consensual physical and sexual encounters. Having a caretaker does not make someone legally the same as a child. Knowing how to talk about bodies, sex, and touch makes everyone safer. And when in doubt, it’s best to reach out.

Written by Anna Clements

Sources:

[i] American Psychological Association: https://www.apa.org/topics/violence/women-disabilities

[ii] Nixon, Jennifer “Defining the Issue: the Intersection of Domestic Abuse and Disability,” Social Policy and Society 8:4, 475–485 accessed: https://www-cambridge-org.resources.library.brandeis.edu/core/services/aop-cambridge-core/content/view/0840E20F54B146E89CA452D1D6FD1BB1/S1474746409990054a.pdf/defining_the_issue_the_intersection_of_domestic_abuse_and_disability.pdf

[iii] National Center for Biotechnical Information: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4692458/pdf/nihms745956.pdf

[iv] Nixon, “Defining the Issue: the Intersection of Domestic Abuse and Disability”

[v] Author’s note: I have personal experience working at a residential living facility for people with disabilities, and with having a disability, and some of these situations are based on my observations and experiences.

[vi] Mental Health Code Excerpt, Act 258 of 1974, Chapter 7 and 7A, accessed: https://www.michigan.gov/documents/mdhhs/MHC_Excerpt_Chptr_7-7A_621181_7.pdf

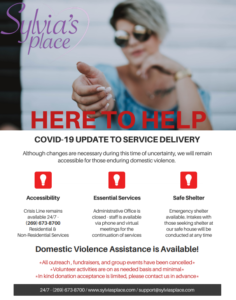

COVID-19 poses new and particular problems for people experiencing abuse.

While people stay home to stay safe from COVID-19, they may be protected from the virus, but other harms can increase: namely, domestic violence. As long as the virus makes it unsafe to be in public spaces, people facing physical, emotional, or psychological violence from those they live with face a difficult dilemma of whether to stay at home and risk abuse, or leave home and risk exposure to the virus. Furthermore, a lot of the safe public spaces that used to be places where people could go to escape violence in the home are not currently open.

Although it is impossible to have precise numbers on the topic, because many cases of abuse are not reported, the World Health Organization has stated that domestic partner abuse has increased significantly in the United States since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. Being quarantined with their perpetrators puts people at an increased risk for violence; abusers who are stressed are often more prone to lashing out. But this does not mean that COVID-19 is to blame for their behavior; abuse is a conscious decision and is always the abuser’s fault.

Forced isolation due to a pandemic can introduce new types and experiences of abuse, and sometimes, ones which people might not immediately recognize as abuse. If someone is threatening your health or the health of loved ones by deliberately exposing you or them to the virus, then that is a form of abuse. If someone is forcing or pressuring you to do things that feel unsafe, then that is a form of abuse. If someone is controlling your access to money, food, or other things that you need, then that is a form of abuse.

Forced isolation due to a pandemic can introduce new types and experiences of abuse, and sometimes, ones which people might not immediately recognize as abuse. If someone is threatening your health or the health of loved ones by deliberately exposing you or them to the virus, then that is a form of abuse. If someone is forcing or pressuring you to do things that feel unsafe, then that is a form of abuse. If someone is controlling your access to money, food, or other things that you need, then that is a form of abuse.

If an adult in your household needs help, but is putting others at risk through their behavior, then it is not your job to help them on your own. Southwest Michigan has a variety of services for different types of crises; knowing what they do and how to contact them is one thing that all of us can do to make ourselves safer and better able to help those who are in danger. If you or someone you know is experiencing abuse, whether it is physical, sexual, emotional, or financial abuse, it is important to reach out to someone ASAP.

Here are a few of the resources in Southwest Michigan that can help:

For help with situations of abuse, call:

Sylvia’s Place, located in Allegan.

Sylvia’s Place offers a crisis shelter and a 24-hour crisis line, at (269) 673-8700 or 888-411-7837

Kalamazoo YWCA, located in downtown Kalamazoo.

The Kalamazoo YWCA has a crisis shelter, located at 353 E. Michigan Ave, 49007, a 24-hour domestic violence hotline, at (269) 385-3587, and a 24-hour sexual assault hotline, at (269) 385-3587.

If you or someone you know is experiencing a mental health crisis, then you or they can call these numbers:

Allegan County Community Mental Health, located in Allegan.

ACCMHS has a hotline that is open 24 hours a day, at (269) 673-0202 or (888) 354-0596. Although the doors to the building are closed during the pandemic, their services are available over the phone an online, at www.accmhs.org.

Gryphon Place, located in Kalamazoo.

Gryphon place has a 24-hour crisis hotline, at (269) 381-4357. Their trained staff and volunteers are experienced in talking people through mental health crises including suicidal thoughts. If someone in your household is experiencing a mental health crisis and does not want to call, you can call the crisis hotline and they can talk you through steps to making sure that everyone is safe.

National Suicide Prevention Hotline: 1-800-273-8255.

If you or someone you know needs food, medical assistance, or other essential resources:

Allegan County Food Pantry Collaborative includes a network of member food pantries that offer food through scheduled drop-off or pick-up, at locations all around the county: https://alleganfoundation.org/allegan-county-community-foundation-covid-19-response-information/

For more information on local resources, call the United Way resource hotline, at 2-1-1. This recorded hotline provides information on COVID-19 resources, food pantries, shelter, and medical assistance.

The most important thing to remember is that there is always help available. You are not alone. Knowing where to call for help could make all the difference, because no one can know when the need will arise to make the call, for yourself or for someone else.

Be safe; be informed.

Written by Anna Clements

Join us for a Fourth of July Cookout…

to support victims of domestic violence!

When: July 5, 6, & 7th

Where: The Root Beer Barrel

455 West Center St

Douglas, MI

Bring your friends and family out, enjoy a burger while supporting a great cause! We hope to see you there 🙂

Learn more about this event on Facebook:

https://www.facebook.com/events/374715616515693/

This year, as you drape the twinkling lights and hang your stockings from the mantel, take into consideration that not everyone honors a season of peace, love, and tranquility. Unfortunately, the holidays can be an even more dangerous time than normal for those at risk for domestic violence. From the financial burdens of gift buying to an overall increase in alcohol consumption, to a flurry of emotions—and sometimes stress—that accompany a plethora of family togetherness time, there are many reasons why the chance of intimate partner violence can increase during the holidays.

Although statistics of actual incoming calls on the day of a holiday may not resemble this theory, survivors themselves can attest that danger heightens and fear emanates. Most victims of abuse will dread the holiday season as it approaches versus embrace this joyous time of year.

“When the holiday time would come, I would cringe with just the thought of asking my husband to spend money on gifts or attend a family function. I would hope for the best, but the outcome would always be the same…terror and anxiety. Christmas was never a good day in our house.” ~Brooklyn

Whether survivors do not want to disturb family cohesiveness on these days, or lack private time to make a call for support, the decline in calls is not necessarily an indication that violence ceases on these days. The majority of agencies such as ours would more than likely agree that calls will often increase above normal levels the days and weeks immediately following a holiday. Many times survivors of abuse do not want to disturb family traditions or separate children from their family during a holiday, regardless of abuse that may be occurring.

“I was praying that the holidays would brighten my boyfriend’s mood, bring new light to our relationship, make him happy because it surely seemed like nothing I did worked. I bought him something very special to show how much he meant to me. He thanked me by giving me a broken nose. I made the decision that day to leave as soon as I could. It was two days before he left me alone and I could make the call…I reached out, got help and never looked back. I encourage anyone in that situation to do the same. It’s not worth your life.” ~ Tessa

What can you do? If you are currently with an abusive partner, reach out to us. We are here, 24/7 ~ 365 days a year. And, remember, you do not need to figure out an escape plan right away—you can simply call to talk. We are here to help every step of the way or to just listen. If you are unable to call safely from home, call from a trusted friend’s house, your doctor’s office or a public library.

If you suspect someone close to you is the victim of an abusive partner, watch for signs such as possessiveness, rigid gender roles, and financial control. Abuse is not always physical, often there are no visible bruises left behind but internal emotional struggles will exist. To support a victim be non-judgmental and supportive. Listen to them, trust them and empower them. Our crisis line is also available for those looking for advice on how to help a friend, family, or neighbor. If you are unsure what to do or how to help give us a call! We are always available: 269-673-8700

Our needs list is available at Amazon.com!

Updated regularly to ensure our most current needs are easily accessible for those interested in helping out!

Don’t forget…sign up to support Sylvia’s Place with Amazon Smile! You shop, Amazon gives!

Leslie shares a powerful message in this video. She answers the frequently asked question of “Why don’t they just leave?” from a survivor’s perspective and we send our praise to her for her courage and bravery! The “magical atmosphere of trust” her abuser gained over her is not uncommon or unique. The sad truth is that victims suffer from it every minute of every day. We are here when you or someone you know is ready to break the silence! ❤️ Call today (269) 673-8700…an advocate is available to talk or answer your questions 24/7!

Sylvia’s Blog

- Comorbid Dangers: Financial Abuse November 4, 2024

- Comorbid Dangers: Domestic Violence & Animal Abuse September 16, 2024

- Mental Health Awareness Month June 25, 2024

HOURS

Office:

24/7

CONTACT

Administration Office/

Non Residential Services:

269.673.5742

24 Hour Crisis Line:

269.673.8700

PO Box 13

650 Grand St

Allegan, MI 49010

Email:

support@sylviasplace.com